Alongside grantmaking, part of our work at Guerrilla entails engaging people of financial wealth in conversations about our radical approach to philanthropy, in the hope that this helps move resources to grassroots social movements and attention to the need for a Just Transition. Many of the people we speak to in that capacity have expressed an interest in Effective Altruism (EA) and some even cite it as a reason why they won’t support grassroots activism. That’s enough reason to share some of our thinking about where we believe EA adds to the philanthropic landscape and where it fails to encourage a deeper, much-needed reflection.

What is EA and what can be learned from it?

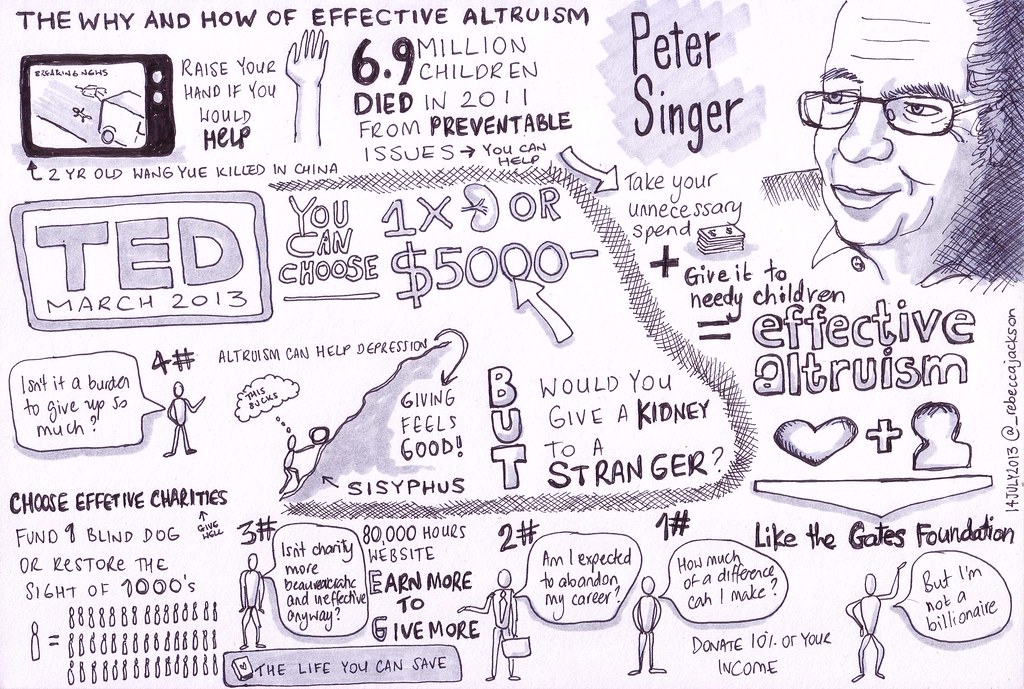

EA is a movement popularised by Peter Singer and other philosophers and has been taken up by some major philanthropists. There’s a pretty good website where you can learn all about the approach in detail. The basic question EA invites you to ask is ‘How can you create the most good in the world with the time or money you give?’. If you agree with that question and believe that ‘the most good’ can be objectively measured, you might be inclined to join the effective altruists in trying to be as ‘impartial’ and ‘science-aligned’ as possible to find the correct answer.

So far so good. Old school philanthropy or traditional charity is about the benevolent philanthropist sharing their wealth with those that are deemed deserving. Funding decisions are often based on personal relationships or emotional connections to a cause, sometimes invoked by dramatic images of suffering and grounded in moral obligation (the duty of ‘giving back to the community’). In the worst case, funding excludes grantees who can’t or won’t fit into the mould carved out by those with financial power, or supports organizations that cement that power further while providing a convenient altruistic image (read Anand Giridharadas book Winner Takes All for further reflections on why such philanthropy might be doing more harm than good).

EA challenges philanthropists to go beyond funding ‘pet projects’ that they have a personal connection to or serving ‘attractive’ populations (children, cute animals). EA adds to the moral duty to donate a focus on neglected issues with high impact potential and those where additional resources will contribute to their solution (referred to as neglectedness, scalability and tractability in EA lingo). Based on these criteria, some classic issues that EA promotes as effective arenas to achieve benefits for people and planet at a massive scale are: mitigating global catastrophic risks from pandemics (EA promoters can today rightly say ‘I told you so!’) and advanced artificial intelligence, ending factory farming, or saving millions of lives in developing countries for diseases that can be cheaply and effectively treated. Organisations that are building the EA field (e.g. Open Philanthropy in the US and Effective Giving in Europe) also conduct in-depth research to compare the effectiveness of different approaches to tackle those issues, sharing their findings openly to maximise influence and improve overall decision-making in the field. This is a practice that traditional philanthropy can learn from.

In summary, EA rightly points out the missed opportunity for traditional philanthropy to maximize its impact because it primarily relies on emotional choices and assumptions about what works with little rigorous analysis. It guides philanthropists who want to maximize their impact by taking what EA describes as an ‘impartial’ and ‘science-aligned’ approach to selecting causes and measuring the effects of their donations.

There is something dogmatic, though, about the religiousness with which some proponents of EA – especially the more naive neo-converts donating via GiveWell – describe it as the only approach to decide how philanthropic resources should be allocated. EA’s approach of doing ‘the most good you can now’ without, in our opinion, questioning enough the power relationships that got us to the current broken socio-economic system, stands at odds with the Guerrilla Foundation’s approach. Instead, we are proponents of radical social justice philanthropy, which aims to target the root causes of the very system that has produced the symptoms that much of philanthropy, including EA, is trying to treat (also see here and here).

Below we outline our four pain points with EA. First, EA replicates a specific set of problematic values that might contribute to cement the current broken system. This results in a focus on ‘doing maximum good now’ over an analysis of root causes and power dynamics, which is our second point. Third, at the level of wealth owners, EA, with its ‘pseudo impartiality’, might shield them from a deeper scrutiny about the origins of the money they’re giving away. Related to this and finally, EA’s fear of ‘warm glow’ grant-giving also seems to stand in the way of taking into account trust-building and human relationships as key ingredients to finding the most effective solutions we need to the world’s biggest problems.

EA is deeply rooted in the values underpinning the current system

‘Where do I get the most bang for the buck?’ ‘Which issues are large in scale, i.e. which issues (have the potential to) create suffering for a lot of sentient beings (think factory farming or global poverty)? Which of those issues are the most neglected and tractable and are thus most important?’ and ‘Is there a scientifically proven effective solution to solve those issues? If not, can EA experts make a rigorously assessed case for a potentially effective solution with measurable impacts?’ These are essentially the questions asked by EA to determine which issues and approaches should receive philanthropic support.

By asking these questions, EA seems to unquestioningly replicate the values of the old system: efficiency and cost-effectiveness, growth/scale, linearity, science and objectivity, individualism, and decision-making by experts/elites. No wonder the approach is being embraced by many who have most benefited from a system that centres on these values: young, well-educated inheritors, Silicon Valley folks and entrepreneurial types. EA is grounded in the same kind of efficiency and scale thinking that leads to the establishment of factory farming – a practice that EA so desperately seeks to end because it results in the suffering of billions of animals. We feel compelled to go back to an often-cited Audre Lorde quote:

“For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change.”

EA privileges practices that are ‘trying to beat the Master in his own game’: either already tested approaches, or academically-identified interventions with measurable outcomes that can be scaled. Even though some EA practitioners might emphasise the open-endedness of EA’s search for solutions, the technocratic nature of the approach itself will only very rarely result in more funds going to the type of social justice philanthropy that we support with the Guerrilla Foundation – simply because the effects of such work are less easy to measure and they are less prominent among the Western, educated elites that make up the majority of the EA movement.

EA’s premise that ‘it is wrong to do much less good rather than much more if doing more is no costlier to you’ is undoubtedly alluring. However, we question whether less readily measurable social change goals like fairness, justice or anti-oppression are, in practice, being ignored by a methodology that favours very concrete outputs and outcomes.

‘Do maximum good now’ taking the system as given, not questioning root causes or power structures

During a 3 day ’Intro to EA’ course, Paolo was kept busy learning from ‘experts’ about the most exciting neglected issues and effective solutions. At no point, however, was he challenged there to think about what is at the root cause of all the suffering that you are about to end with EA grants, or how to build a more equal democratic society that might not produce these evils in the first place.

Focusing the attention on expected impact calculations about whether it is more effective to use philanthropic dollars to provide mosquito nets or chloroquine, or HIV/AIDS education vs. antiretroviral treatment, misses out on much broader questions: What are the structural, economic and political factors that abet the spread of these and other diseases in certain parts of the world? Why would you seek to prolong the lives of individuals if you don’t address the high chance that the lives you saved end up as bodies in the Mediterranean after trying to escape climate change-induced drought and famine, dictatorships and war – all of which are one way or another caused by rich Northern countries? Are we left to focus on largely maintaining the status quo by reducing misery, making it just bearable enough, but not questioning the root causes of trauma, exploitation, and planetary collapse?

These are the questions that arise when confronted with an approach that gets promoted by highly trained, philanthropist-backed elites in white shirts as the scientifically correct, data-driven or forecast-based, rational choice for the informed conscious philanthropist of the new millennium. If EA practitioners paid more attention to the root causes of the accumulation of wealth & power, exploitation and suffering, it might contribute to creating a new world where, in the long run, philanthropy is needed to a much lesser extent. Take problems such as ending factory farming or unsafe AI (two of EA’s core causes): if all investment was directed in a responsible way towards plant-based alternatives, and towards safe AI, would we need philanthropy at all? However, because this meta-objective is so abstract, long term, and hard to measure, EA misses out on this more holistic and long-term approach to not just patching up, but eventually solving the very causes identified as pressing. What is the point of accumulating wealth through a system that creates the problems you are trying to solve with (effective) philanthropy? Shouldn’t wealth owners first, at the very least, be sure to have engaged in reparations for past wrongs (an issue that increasingly receives attention right now), act consciously to produce wealth for the many and not the few, through a more just and regenerative economy, and then and only then, think about how to maximize the impact of their philanthropic giving? Many wealth owners nowadays skip steps one and two and move directly to the latter.

One who does not is Farhad Ebrahimi, the founder of the Chorus Foundation, which started out as a traditional single-issue climate funder. A couple of years into his spending down plan for the foundation (!) he shares one of their main lessons learned arguing that their work is not about “identifying the best policy or the most promising technology or the scariest science” (which is what EA would focus on) but that it’s about “generating the political will to enact the best policy, adopt the most promising technology and heed the scariest science“. This means a more radical, root-cause oriented approach to philanthropy oriented towards a just transition. It involves building political and cultural power to change the goals of the system (e.g. from maximum wealth generation for a few, to wellbeing for all), opposing and breaking power where it is unchallenged and concentrated, building grassroots power and providing the funding for the creation of bold alternatives to the current system.

We acknowledge that the EA community sometimes supports advocacy and political work, for example when it comes to US prison reform, ending factory farming and managing risks from emerging exponential technologies. However, to our knowledge, those approaches still take existing power structures as a ‘given’ and only try to extract incremental change. If we really want to focus on what’s being neglected, we should refrain from putting all our philanthropic eggs in the same basket consisting of approaches to treating symptoms of a broken system. More philanthropic funding, about half of it we would argue, should go to initiatives that are still small, unproven and/or academically ‘unprovable’, that tackle the system rather than the symptoms, and adopt a grassroots, participatory bottom-up approach to finding alternative solutions, which might bear more plentiful fruit in the long run.

Digging deep – but where?

EA’s focus on maximizing impact through its unemotional data-driven approach seems to sit well with inheritors who deep down know that they don’t own their wealth because they never worked for it or, in the case of entrepreneurs, because they are aware that it is disproportionate to the effort that was put in to generate it and that they are benefitting from an unfair system that does not deduct negative externalities. In our interactions with them, we have unfortunately observed that EA practitioners rush to provide donors with a seemingly ‘impartial’ way of allocating wealth and finding meaning and relief in figuring out how one can ‘do the most good for as many sentient beings as possible’. This practically results in wealthy EA donors not going through a (potentially painful) personal development process to confront and come to terms with the origins of their wealth and privilege: the racial, class, and gender biases that are at the root of a productive system that has provided them with financial wealth, and their (often inadvertent) role in maintaining such systems of exploitation and oppression. In her detailed critical analysis of EA, Jennifer Rubenstein uses the term ‘hidden curriculum’ to describe how EA might cement current inequalities. After all, it feeds into an illusion of meritocracy among the wealthy: EA allows you to distinguish yourself from the ‘normal’ Giving Pledge or impact investing crowd with their mantra of ‘doing well by doing good’ because you are ‘doing the maximum good with your wealth’. This might provide those who are already in power with an affirmative ‘saviour narrative’ and prevents any questioning of the broader systems that are breeding the wealth inequality that allows for individuals to see themselves as saviours of millions of lives.

The philosophy and approach of philanthropic organisations like Resource Generation, Solidaire, or 1000 Currents stand in stark contrast to EA’s approach. They provide a process and support framework for people of financial wealth that addresses exactly the problematic systems that are at the root of their privilege and politicises people whose position in the world usually allows them to be a-political. Over the past years, we learned that Guerrilla’s form of social justice philanthropy can be a great tool to make people of wealth more aware of their privilege and responsibility to acknowledge it. As far as we are aware, nothing comparable can be said about any of the EA-based workshops for wealth owners. In fact, Rubinstein in the article cited above even identifies an “anti-political sensibility” in two of the main books written on EA in the past years.

This aligns with Paolo’s personal experience. He was repeatedly told in EA seminars to invest in a more “socially neutral” way instead of ‘wasting’ time and resources scrutinizing the potential negative impacts of his investments, or proactively targeting positive impact investment opportunities. The assumption that there is something like a ‘socially neutral’ investment speaks at length to EA’s lack of a social justice focus, which would argue that every investment either contributes to exacerbate the social and environmental damage of the current financial system or – preferably – achieves the opposite by reforming it. The quest for neutrality also ignores our shared humanity and the interconnectedness of all life on this planet, thereby preventing empathy for and solidarity with those who aren’t as well off as you.

In short, we believe that EA could do more to encourage wealth owners to dig deep to transform themselves to build meaningful relationships and political allyship that are needed for change at the systems level.

It’s the relationships, stupid!

We understand the value of scientifically identifying neglected issues and effective solutions but believe that there is a danger in stopping there. The past years of working with activists and thinking about how social change happens have brought us to realise the importance of relationships, place, serendipity, and emergent complex change. We were early supporters of Extinction Rebellion and witnessed its staggering growth from a crazy idea by a couple of long-term activists into a global movement that not only has put climate emergency on the political agenda once and forever but also is influencing activist discourse about movement building, leadership and ways of relating to themselves, others and the world. Making this early grant was only possible because of a relationship we had built with Roger Hallam, one of the co-founders, our trust in the strong commitment and different strengths brought by the core team, as well as the novelty of some of the ideas underpinning the organisation which we felt might draw more attention to the climate cause. Neither we nor they had any way of forecasting or quantifying the possible impact of the group and we were prepared to ‘at worst’ resource a couple of people who we felt could benefit from a little financial support even if the only thing this would achieve was to fuel their relentless personal quest for social change. How does this assessment process map onto EA’s criticism of ‘warm glow’ or biased giving? How could anyone forecast the recruitment of thousands of committed new climate activists around the world, the declarations of climate emergency and the boost for NonViolentDirectAction strategies across the climate movement?

The concept of warm data captures interrelationships, processes and patterns of complex systems and might be more helpful in understanding the complexities of social change. It might help us reduce the blind spots that come with the rational scientific approach of the EA movement and deliver more precious insights into how to foster systems-level change. Participatory, grassroots-driven social action and movements tackling multiple intersecting forms of oppression are already in themselves positive outcomes that we hope to contribute to. In the long run, these processes change societies by influencing value systems and the ways in which we relate with ourselves, each other and the world and, ultimately, influencing the structures we surround ourselves with.

Finally, because EA is a rather young movement, the jury is still out as to whether the excitement of ‘impartially’ at creating the maximum impact with one’s wealth wears off after a while. We would suspect that donors and grant managers with a deep emotional connection to their work and an actual interest to have their personal lives, values and relationships be touched by it will stick with it and go the extra mile to make a positive contribution, generating even more positive outcomes and impact.

Wrapping it up

We appreciate EA’s focus on thoughtful giving that centres on maximizing real-world outcomes and not the warm-glow of the giver. We also agree with the probability of impact being highest with cause areas that are large in scale (we take this one step further, to the system level), neglectedness (we love focusing on what others fail to attend to, e.g. by making very early-stage grants to small grassroots activist collectives in underfunded geographies like Eastern Europe), but it’s the solvability piece that remains thorny: while we look for the most promising paths to addressing systemic issues, complex systems change can most often emerge gradually and not be pre-identified ‘scientifically’. We identify grassroots groups with a systemic analysis of their issues, bold ideas and lived experience of the problems they are out to tackle. We build relationships with our grantee partners as we collaboratively try to make sense of the issues they’re working on and accompany them on their journey towards impact. In that sense, a diversity of approaches, experimentation and an emphasis on feedback loops and learning are key, as is a degree of gut feeling. We hope to contribute to a Just Transition that can truly have ripple effects and maybe put most of philanthropy out of business for good.

While we appreciate a large deal of the EA approach and the added rigour it introduced into the philanthropic debate, we reject its dogmatic adoption by some, and criticise four fundamental issues of EA, namely:

- It is deeply grounded in the values that could be further cementing our current broken socio-economic system

- It somewhat disregards root causes, issues of power, and systems-level change driven by grassroots movements.

- It provides wealth owners with a saviour narrative and a ‘veil of impartiality’ that might hinder deeper scrutiny into the origins of philanthropic money, and stifle personal transformation and solidarity.

- It ignores the importance of ‘warm data’ in understanding systems change and the role of trust, human relationships, and grassroots participatory action as ingredients for the Just Transition.