Throw a brick through the window of a bank, and you’re a criminal. Own the bank and decide who gets the money, and you’re a philanthropist. This power to decide: who is worthy, what is radical, which futures get funded, is the final bastion of hierarchical control in a sector increasingly fluent in the language of justice (however, less fluent in its application). In the patinated halls of philanthropy, ‘participation’ has become a mainstay of discourse, a safe buzzword that too often masks a refusal to actually cede power (Villanueva, 2021 & Deeper Inquiry #16). Against this backdrop of talk without action, the Guerrilla Foundation (GF) operates not as a benevolent grantor but as a ‘justice-informed grassroots social movement funder’ engaged in a live, messy, and radically transparent experiment: to dismantle the master’s house using the master’s tools, and to build something new, sociocratic, and truly distributed in the rubble.

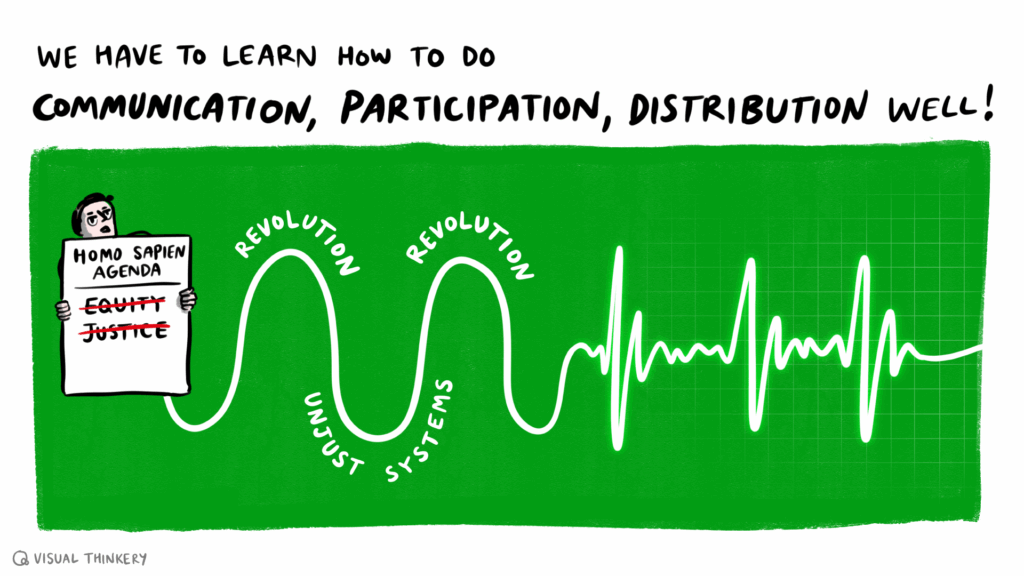

This essay excavates GF’s two-year trial of participatory grantmaking (PGM), a deliberate and gritty effort to shift from a model of charity to one of solidarity and from centralized control to distributed power. It’s a case study in what happens when the abstract desire to “shift power” collides with the material realities of funding across Europe with an intersectional lens (Kaba, 2021). This is not a polished success story; it’s a report from the front lines, complete with failures, tensions, and some punk-rock commitment to learning in public.

I. The Theory: From Talking Power to Moving Power

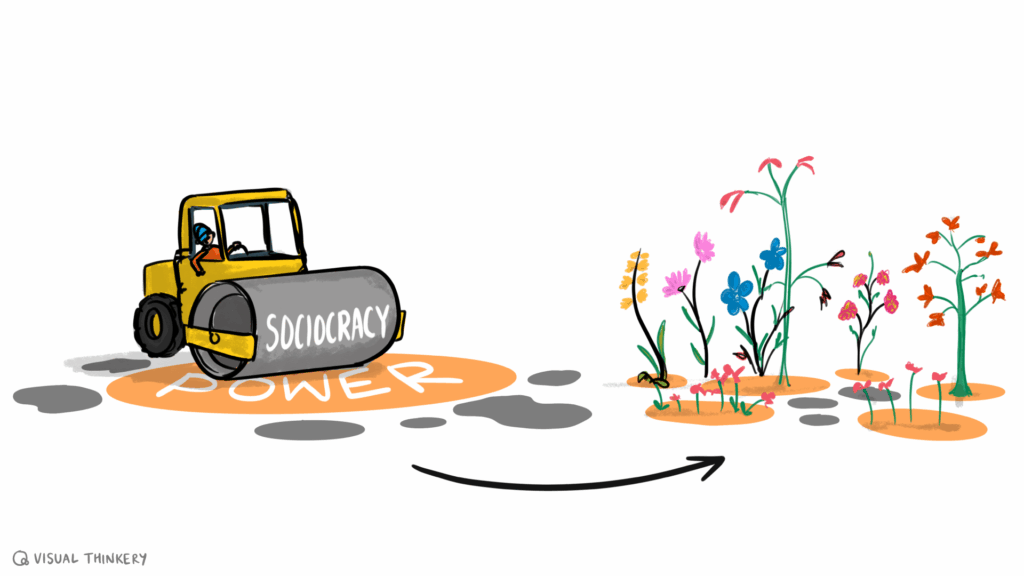

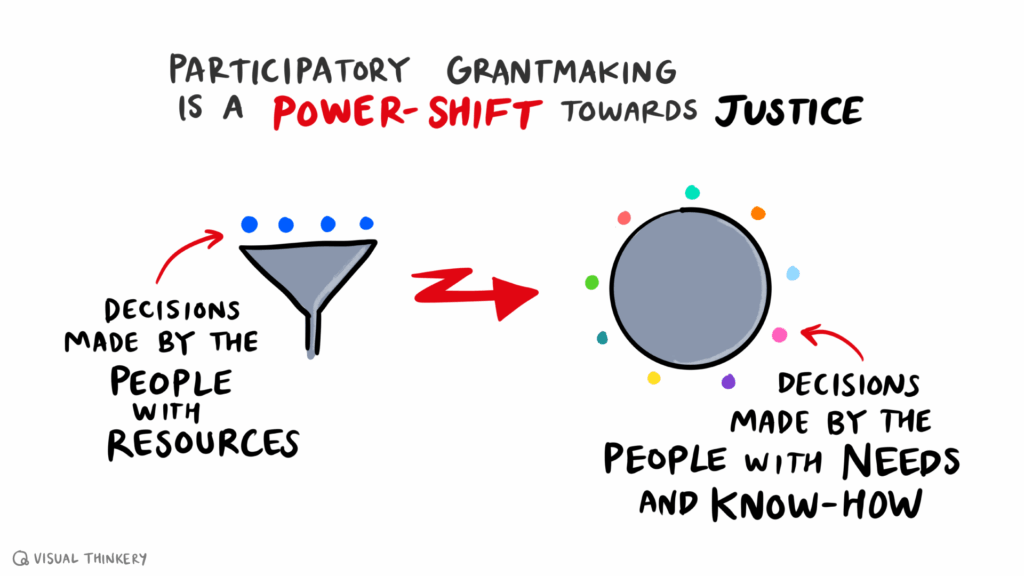

The impetus for GF’s transformation was a fundamental rejection of philanthropy’s inherent paternalism, a system built on what Edgar Villanueva terms the “bloodline of wealth” tainted by colonialism and extraction (Villanueva, 2021). The goal was audacious: to actively make the current form of philanthropy obsolete by redefining the foundation’s role as a “tool for redistribution towards a different society” (Deeper Inquiry #16). This wasn’t about improving efficiency or ‘grantee relationships’; it was about instigating a takeover of the funding apparatus by the very communities it purported to serve, aligning with the long-held abolitionist question of whether oppressive structures can be reformed or must be dismantled (Kaba, 2021).

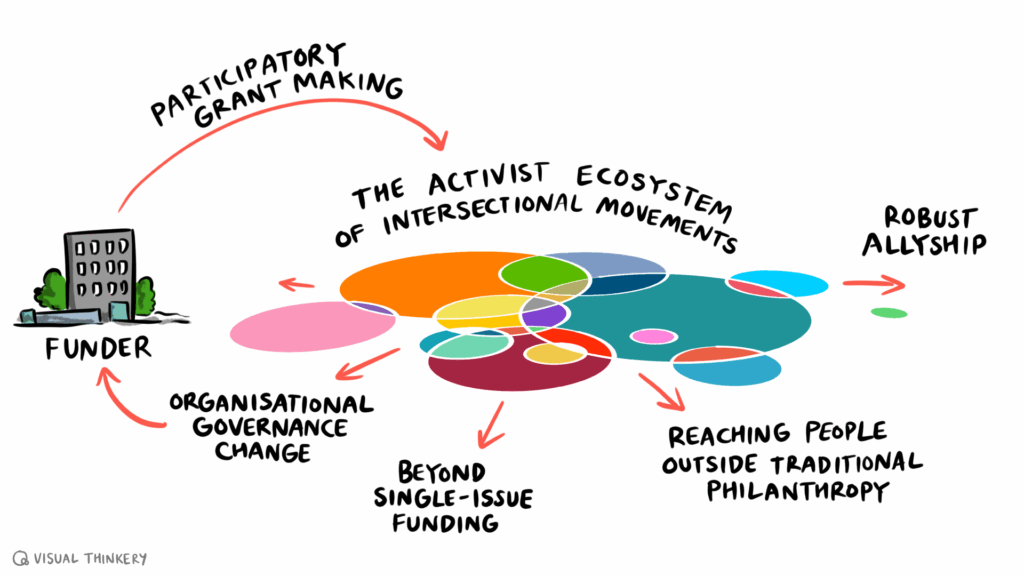

The vehicle for this was the establishment of an Activist Council (AC), a 15-strong body of activists from across Europe, representing a plurality of struggles, geographies, and backgrounds. This model draws directly from the principles of community-led funding articulated by practitioners like the Edge Fund and AORTA, who argue that those directly impacted by systems of oppression are best positioned to make decisions about resources (Shutt, 2019; AORTA, 2017). In the new model, the AC became the sovereign decision-maker for Action grants, while the staff shifted from gatekeepers to “executors.” This structural schism was the first concrete move to decentralize governance, creating a clear line between those who hold lived experience of the frontlines (the AC) and those who hold operational capacity (the team).

II. The Praxis: The Gritty Reality of Distributed Decision-Making

The theory is clean. The practice is anything but. GF’s 2024 evaluation, conducted after the two-year trial, revealed the gritty fissures between ambition and reality, echoing challenges documented across the participatory field (Bajracharya & Gallegos-Reich, 2020).

- The Participation-Speed Paradox: Distributed decision-making is slow. The need for pluralistic consensus clashed with the urgent needs of grantees. The team often became a “bottleneck,” wrestling with the admin aftermath of flexible, AC-driven choices. The solution wasn’t to recentralize but to create clearer structures upon examining where participation is necessary and advantageous and where processes can be iterative, or simply where decisions pertain to a given-circle only. We enter the nexus of trust-based decentralisation where circles keep evolving their thinking around how we do things in each circle and who needs to know what, when, and why.

- The Myth of the Omniscient Collective: How can 15 people possess the deep, intersectional expertise needed to judge a pan-European portfolio? They can’t. The evaluation forced a confrontation with this limitation, a common tension in PGM where representation is always partial (Bajracharya & Gallegos-Reich, 2020). The response was not despair but adaptation: revamping scouting processes with high AC involvement, creating clearer selection criteria, and tagging data to better map their coverage and blind spots.

- The Culture of ‘Unlearning’: Decentralizing structure is futile without decentralizing mindset. Team members had to unlearn the “reflex to decide,” consciously resisting the urge to solve problems themselves – a process of undoing internalized hierarchies. AC members, many new to philanthropy, grappled with imposter syndrome and the uncomfortable weight of becoming “gatekeepers,” a known psychological barrier to shared power (Wright, 2020). This required continuous collective upskilling and a culture built on radical trust, not just a new org chart.

III. The Contradictions: Navigating the Grey Areas

A punky ethos thrives in contradiction, and GF’s model is rife with them. These are not failures but the very sites of learning.

- Structure vs. Flexibility: How to balance a fair, transparent process with the need for fluid, context-specific exceptions? “Grey areas” like solidarity funds or special requests created tension. The answer is not a rigid rulebook but a continuous negotiation, a “trade-off” that acknowledges the inherent messiness of redistribution, a challenge familiar to any group practicing horizontalism (Sitrin, 2006).

- Visibility vs. Protection: Should AC members be hyper-visible to grantees, fostering transparency, or protected from being bombarded with requests? This tension between open doors and activist burnout remains a live wire, highlighting the non-monetary costs of participation that funders must account for (Graham & Goddard, 2022).

- Grantmaking vs. Governance: The most profound revelation was that you cannot decentralize grantmaking in a vacuum. It acts as a “trojan horse” for wider systemic change (Deeper Inquiry #16). Questions erupted: If the AC decides grants, who decides the grantmaking budget? Is the FC merely a “cash-machine”? This PGM trial exposed the unresolved hierarchies in the wider governance model, directly catalyzing GF’s ongoing, even more radical, journey into full sociocracy (Buck & Endenburg, 2012) and a decentralised circle structure, proving that ceding control in one area inevitably raises the question of control everywhere.

IV. The Horizon: From Experiment to Default

GF’s journey reframes the question from “Is this participatory?” to “How participatory can we be, and what are we building towards?” Our evolution points to a future of a “bigger tent”, engaging more activists as reviewers to map a wider range of issues and geographies in our grantmaking, while perhaps refining a smaller core AC for governance. It suggests using grantees ourselves as scouts, asking for ecosystem recommendations to break down the competition that funding often creates, an approach that begins to embody the “solidarity not charity” ethos (Dixon, 2014).

The conclusion is as punchy as its premise: PGM is not a grantmaking tactic; it is a gateway drug to political transformation within an organization. It is fundamentally incompatible with top-down governance. By choosing this path, the Guerrilla Foundation has committed to a permanent state of becoming, a continuous and unruly process of questioning power, redistributing control, and building a praxis that is as radical as the movements it funds. We are not just pushing the bar on participation; we are throwing the bar out the window and inviting everyone to help build a new one from the ground up.

Who’s in? 🙂

References

AORTA (Anti-Oppression Resource & Training Alliance). (2017). Democratic Decision-Making AORTA Resource.

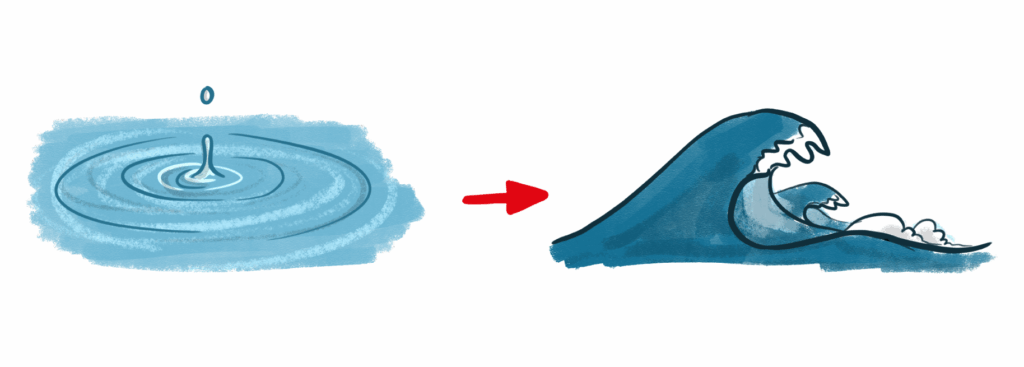

Bajracharya, D., & Gallegos-Reich, C. (2020). Participatory Grantmaking: A Wave of Change?. The Commons.

Buck, J., & Endenburg, G. (2012). The Creative Forces of Self-Governance: The Principles of Sociocracy. Sociocracy.info.

Dixon, E. (2014). Solidarity Not Charity: Mutual Aid for Mobilization and Survival. Truthout.

Incite! (2007). The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex. South End Press.

Kaba, M. (2021). We Do This ‘Til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transforming Justice. Haymarket Books.

Sitrin, M. (2006). Horizontalism: Voices of Popular Power in Argentina. AK Press.

Shutt, C. (2019). The Grammar of Power: A Guide to Decentralised Decision-Making and Participatory Grantmaking. The Edge Fund.

Villanueva, E. (2021). Decolonizing Wealth: Indigenous Wisdom to Heal Divides and Restore Balance. Berrett-Koehler Publishers. (2nd Ed.).

Wright, C. (2020). The Psychology of Participatory Grantmaking: Navigating Power and Identity. Nonprofit Quarterly.