We get requests for funding on a daily basis from many different corners of Europe. First of all, this is great news because word has clearly spread about the Guerrilla Foundation since we started three years ago. Naturally, some of these requests are more aligned with what we fund than others. That’s alright. We want to support systems change more broadly and our idea of what that means is evolving. This sometimes makes it hard for potential candidates to figure out whether they should apply to us or not. This blog is intended to provide some help on that front.

We generally believe in treating everyone who approaches us with a request for funding with respect, giving them the attention and feedback they deserve. Raising funds for an idea you believe in can be an uphill battle and very hard on your self-esteem. I get that. I also get that I am writing this blog from a position of power where we, the Guerrilla team & advisors, get to decide who receives money and what in our eyes makes a ‘good’ project.

However, in the past weeks, we received an unusual amount of proposals for new political initiatives by young founder teams. While vastly different in many aspects, these projects shared a couple of off-putting characteristics that I want to summarise here this primer for the benefit of future candidates. Together with other posts about how we believe our foundation can contribute to social change this should give you a pretty good idea about why we do what we do.

The Fish Stinks from the Head

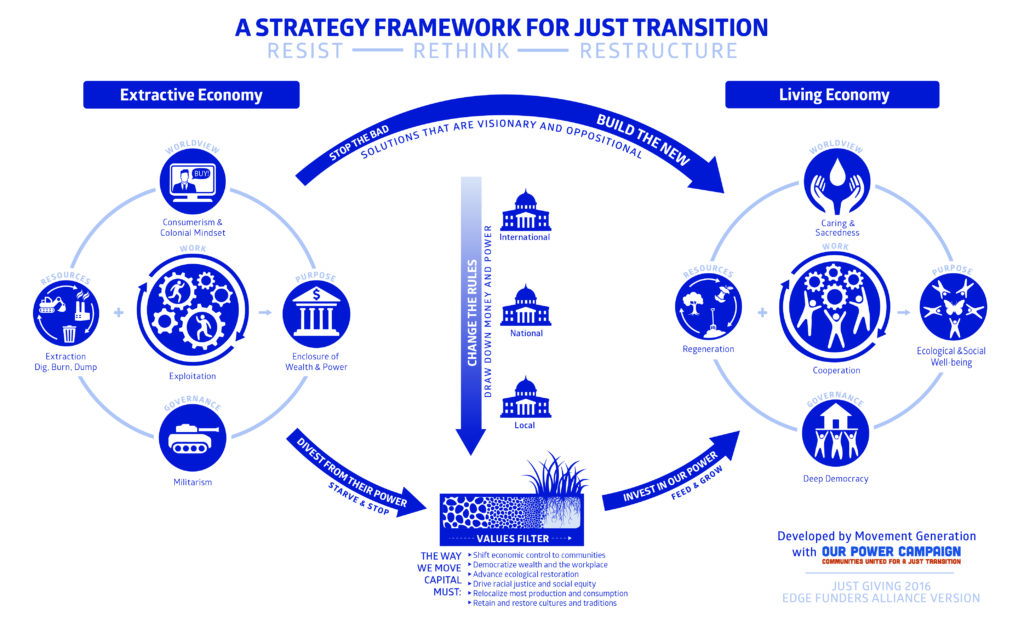

That’s what my grandma always used to say, meaning that if the key people behind an idea don’t believe in, and actually live the change they want to create in the world, the whole ‘fish’ ends up being not of the kind that you want to eat for dinner. Values like shifting power, co-operation and building community are high on our agenda, as we believe they are an essential ingredient for the Just Transition.

When we receive a proposal for funding that reads like a start-up pitch with competitiveness and self-promotion oozing out of every line of text, we naturally ask ourselves how this project can possibly contribute to a shift in what we value as a society and how we imagine our future. Likewise, if your core team and board of advisors are exclusively male, white, and/or upper-middle-class, you are cementing systems of patriarchy and classism rather than challenging them. And no,

the argument that you couldn’t find different kinds of people in your circle of friends just now when you got started, is not an excuse for a lack of diversity. Nor is the promise to ‘diversify the team later’. It’s all about the values that you start with,

i.e. the head of the fish. Also, it’s not enough to have a set of nice-sounding values listed on your website if we don’t see any evidence that you actually live these every day. So ask yourself: Are we, the founding team, replicating old patterns and structural injustices as we embark on our social change journey or are we living our values?

There Are No Unicorns

Unlike in start-up culture, where founders aspire to build unicorn companies, we keep them where they belong: the fantasy world.

We value humility, lived experience and awareness of how your work builds on that of others.

If you claim uniqueness or think you are the movement, we do get wary because you probably sound a wee bit delusional.

There surely are personal and cultural differences in how people self-promote and I feel we do understand different styles of expression. Our application form, for example, doesn’t have a word limit to allow you to keep it flowing in case you’re very excited about what you do. But if your social change project sounds like a start-up pitch, that is hyperpolished, not acknowledging flaws, and talking down the competition, you maybe haven’t understood what you claim to be fighting for.

Social movements (like the women’s, workers or environmental movements) are comprised of numerous organisations and groups. These might vary in terms of tactics and theory of change but are all connected, interdependent and working towards the same wider goal. No organisation will single-handedly solve the complex systemic challenges we are facing. The term movement ecology used by the Ayni Institute summarises this idea pretty well and you might want to watch this intro to movement ecology if you fear you might suffer from unicorn syndrome. Learning from and building on past efforts, knowing where your initiative fits into the larger picture and building bridges to other initiatives in your movement are clear signs for us that you understand your movement ecology.

Don’t get me wrong. Bold ideas are great, but they need to be based on good analysis and solid experience, not unfounded assumptions from unicornland. Also, there is nothing wrong with consciously trying a bold, new approach even if not everyone might agree that this is the right thing to do. But – and that is a big but – people with bold ideas need to be grounded, open to engage, and willing to learn.

A current case in point is Extinction Rebellion. Some might consider the distributed organisation a social change unicorn, given its exponential growth and the attention it has generated in the span of only a year. However, while XR has made an amazing contribution to the climate movement, it wouldn’t have been possible without decades of climate organising, research and campaigning that massively influenced the general public’s knowledge about and attitude towards anthropogenic climate change.

The current critique of XR (e.g. here and here) reflects the need for more bridge-building with other actors in the climate movement. The critique is also a sign that XR is challenging some assumptions of the left more broadly, for example when it comes to the role of spirituality and the centrality of a culture of care. As a whole, this points to a massive potential for learning and development for the climate movement and highlights the importance of engaging within the movement ecology for collective sensemaking and, ultimately, more effective movements. Competitive unicorns unwilling to engage are – to return to my earlier point – recreating problematic mindsets and cultures. Moreover, the risk remains that they will die a quick and unglamourous death, leaving behind masses of disenchanted people who believed in them while they were alive and kicking.

Where Are Your Roots?

We spoke about systems change activism and targeting the root of an issue elsewhere. Here, I want to add my third and final point, which is that your initiative should centre the lived experience of those affected by the issue(s) you aim to address and support voices that are otherwise not heard.

A hypothetical example: if your stated goal is to bring the voices of disadvantaged groups into politics but you have no direct connection to such groups in your founding team and also no strategy on how to reach out to and effectively engage them, that might be an insurmountable challenge for the success of your endeavour. No matter how well-intended and motivated you are and whether you have a great founding team, if you are not willing to go where the problem is and instead you plan your first events in the safe, urban hipster bubble that you’re used to, we will ask you a couple of very challenging questions when you approach us for funding. Of course, it is challenging to actually reach out of your bubble, but if you really want to build bridges, show solidarity and change oppressive systemic patterns, that’s exactly what you need to do. In such cases it’s better to ‘fail early’ and realise that this isn’t what you can realistically do and then go back to the drawing board to think about which communities you can actually connect to and successfully work with.

A Positive Example

To wrap up on an uplifting note with the type of grassroots social movement organising and ecosystem building I’m talking about, I recently came across is It Takes Roots, an initiative from the U.S. It Takes Roots is a collaboration of various grassroots social movements that bring to the fore communities’ solutions to the systemic challenges of creating climate, economic and racial justice. In their words, tackling the climate crisis does ‘require not only decarbonization, but also strategies to decolonize, detoxify, demilitarize, degentrify and democratize our economies and communities.’ It would be great to see more of this type of organising happening in Europe.

We hope you heard our call and we really look forward to hearing from you!