* a Portuguese version of this article is available at the bottom of this page

In Portugal, the Luso-tropicalist idea of ‘tolerance towards diversity’ is still latent in its collective imaginary. The growing power of the extreme right in the Portuguese political sphere proves its existence, making invisible the public debate about racism. To help reverse this trend, activists such as Mamadou Ba (a Guerrilla grantee) and the organisation SOS Racismo, are holding the frontlines in the fight against racism in Portugal.

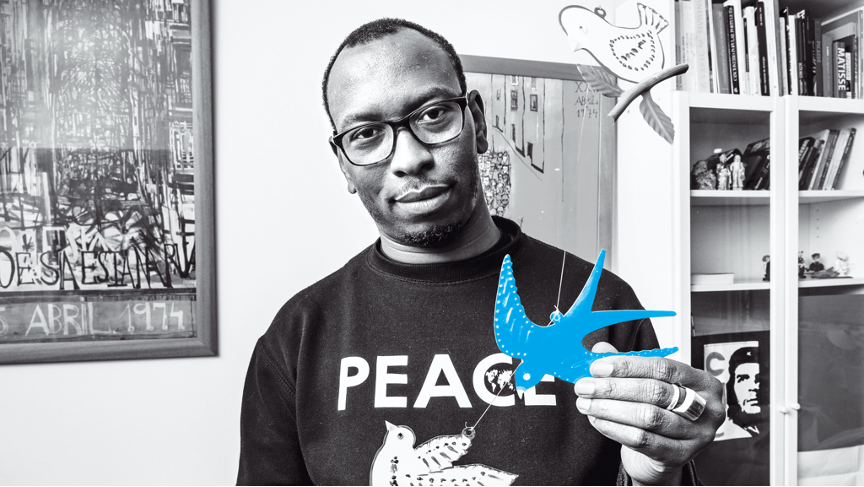

Mamadou is a Portuguese citizen born in Senegal. He is a father, polyglot, Pan-Africanist, and, as he puts it, “a decolonial-anti-racist by condition and conviction”. His wholehearted commitment to the cause led him to be awarded this year’s European Frontline Defender award and, paradoxically, to be hospitalised due to burnout from his activist work. Although he looks at the European award with joy for the recognition of his dedication, he ascribes it to the cause and the collective work that has led to this moment.

He began his activism with SOS in 1996. This organisation aims to help create conditions for the self-organization of racialized people so that they can achieve greater citizen equity. From distant inspirations such as the ten points of the Black Panthers’ manifesto, the association emerged in the context of a reorganization of the Portuguese extreme right that was then gaining shape and strength in Portugal, and in the wake of racial hate crimes against important figures of the anti-racist struggle.

Its intervention in the fight against racism started in schools, as it observed that this was the place where right-wing extremist groups recruited their supporters. To this day, it maintains this focus of action, but the list of initiatives developed extends far and wide, and in an intersectional way. Its work unfolds in autonomous decentralized centres throughout the country, applying a horizontal approach in decision making as well as in its ability to self-organise, whilst encouraging active participation at the national level.

With persistence and networking, SOS Racismo has contributed to the creation of a critical voice in the public sphere to the political apparatus in Portugal, the latter structurally racist and with colonial origins. “Understanding what cultural diversity means in the Portuguese context implies radical actions,” says Mamadou. And what form does this radicality take? Firstly, in breaking the taboo that “Portugal is not a racist country,” an idea that is still present in the collective memory of Portuguese society.

During the interview, Mamadou criticizes the way political action perpetuates and defines the possibility of the existence of a racial system. He notes that, the understanding of public governance is lacking the idea of community, of recognizing the diversity that characterizes Portuguese society, and the perception that spaces are not made for people, but with people. “Any social intervention needs to be done with the people who will benefit from it,” says Mamadou. Drawing from SOS’s experience, Mamadou explains that this systemic arrogance also influences organizations like his, where these embedded vices of detachment can result in biased social interventions. Perhaps we simply lack a greater presence of solidarity and care in our practices, which could help deconstruct such systemic harm.

This is why within SOS Racism creating a culture of care is important, emphasizing the relevance of informal relationships to the struggle. According to Mamadou, “learning to know each other outside of the struggle is absolutely beneficial”, because experiencing the other allows one to understand people in their multiplicities – emotional, affective, or relational – and not only as political activists.

But despite its efforts, care continues to be a topic of inquiry for SOS. In fact, we mentioned above how militancy brought Mamadou to the hospital earlier this year. The truth is that the extractivist logic of the system as well as the voracity of public events demand constant availability from SOS’s members, which, despite its national representation, remains a small association. And now more than ever, the threat of the extreme right and the lack of commitment of society in the fight against racism lead to an enormous pressure for intervention on the movements. Organizations asking questions regarding self-care is essential for contemporary activist movements. Mamadou understands how we quickly prioritize the struggle over personal well-being, but also reminds, “without life, there is no militancy”.

As Mamadou says, when we want to change society for the better, the people who seek to be agents of that change must also be joyful about it. It is important to step out of the extractivist logic that we want to combat, just as it is relevant to cultivate joy in social movements. “Ultimately, the goal of the struggle is happiness, not as a universal idea, but in a way that people can be happy how they want to be. And when they are happy it is because they are not oppressed by anything within the system.”

/ / /

PORTUGUESE VERSION

SOS Racismo e o Combate ao Racismo em Portugal

Em Portugal, a ideia luso-tropicalista de ‘tolerância para com a diversidade’ permanece latente no imaginário coletivo português. A crescente frente da extrema-direita na esfera política portuguesa faz prova da sua existência, tornando invisível o debate público sobre o racismo. Para ajudar inverter esta tendência, conversámos com Mamadou Ba sobre o seu ativismo no seio da organização que faz tremer chão no combate ao racismo em Portugal, a SOS Racismo.

Mamadou é um cidadão português nascido no Senegal. É pai, poliglota, pan-africanista, e, nas suas palavras, “anti-racista decolonial por condição e convicção”. A sua entrega de corpo e alma à causa levou-o a ser premiado como Frontline Defender da Europa este ano e, paradoxalmente, ao internamento hospitalar devido a um burnout pelo trabalho ativista. Embora olhe para o prémio europeu com alegria pelo reconhecimento da sua dedicação, explica que o atribui à causa e ao trabalho coletivo que levou até tal momento.

Começou o seu ativismo junto da SOS em 1996. Esta é uma organização que tem como objetivo ajudar a criar condições para a auto-organização de pessoas racializadas, de forma a que possam obter maior equidade cidadã. De inspirações distantes como os dez pontos do manifesto dos Black Panthers, a associação surge no contexto de uma reorganização da extrema-direita portuguesa que então ganhava forma e força em Portugal, e no seguimento de crimes de ódio racial a personagens importantes da luta anti-racista.

A intervenção do SOS no combate ao racismo começou nas escolas, por observarem que era este o lugar onde grupos extremistas de direita recrutavam seus defensores. Até hoje, mantêm este foco de ação, mas a lista de iniciativas que desenvolvem estende-se por demais, e de forma interseccional. O seu trabalho desdobra-se em núcleos autónomos descentralizados pelo país, aplicando uma horizontalidade nas tomadas de decisão e na capacidade de auto-organização dos núcleos, incitando ainda à participação ativa a nível nacional.

Com persistência e em rede, a SOS Racismo contribuiu para a criação de uma voz crítica no espaço público ao aparato político em Portugal, este último estruturalmente racista e com origens coloniais. “Perceber o que significa a diversidade cultural no contexto português implica ações radicais”, afirma Mamadou. E que forma assume essa radicalidade? Primeiramente, na quebra do tabu “Portugal não é um país racista”, ideia presente na memória coletiva da sociedade portuguesa.

Durante a entrevista, Mamadou critica a forma como a ação política perpetua e define a possibilidade de existência de um sistema racial. Nota que falta no entendimento da governação pública a ideia de comunidade, de reconhecer a diversidade que caracteriza a sociedade portuguesa, e a percepção de que os espaços não se fazem para as pessoas, mas sim com as pessoas. Segundo Mamadou, “Qualquer intervenção social necessita de ser feita com as pessoas que dela vão beneficiar”. Partindo da experiência do SOS, Mamadou explica que esta arrogância sistémica influencia também organizações como a sua, mostrando que desses vícios de distanciamento incorporado podem resultar intervenções sociais preconceituosas. Talvez falte simplesmente uma maior presença da ideia de solidariedade e cuidado nas nossas práticas, que poderiam ajudar a desconstruir tais vícios sistémicos.

É por isso que dentro da SOS Racismo criar uma cultura de cuidado é importante, enfatizando a relevância das relações informais para a luta. Segundo Mamadou, “Aprender a conhecer-se fora do combate é absolutamente útil”, pois experienciar o outro permite entender as pessoas nas suas multiplicidades – emocionais, afetivas, ou relacionais – e não apenas enquanto ativistas políticos.

Porém, o cuidado continua a ser um tema a investigar para o SOS. De facto, acima falávamos de como a militância acabou por levar Mamadou ao hospital. A verdade é que a lógica extractivista do próprio sistema ou a voragem dos acontecimentos públicos exigem constante disponibilidade dos membros do SOS que, apesar da sua representação nacional, permanece uma associação de pequena dimensão. Também hoje, mais que nunca, a ameaça da extrema-direita e a falta de compromisso da sociedade no combate ao racismo leva a uma pressão enorme de intervenção sobre os movimentos. Tal leva a que as organizações esgotem os seus membros, tornando questões como práticas de auto-cuidado temas relevantes. Mamadou entende como é que rapidamente priorizamos a luta face ao bem-estar pessoal, mas relembra, “Sem vida, não há militância”.

Como nos diz Mamadou, quando queremos mudar a sociedade para o melhor, também as pessoas que procuram ser agentes dessa mudança têm de estar alegres com isso. É importante sair da lógica de extrativismo que se quer combater, assim como é relevante cultivar a alegria nos movimentos sociais. “No final de contas, o objetivo da luta é a felicidade, não enquanto ideia universal, mas que as pessoas possam ser felizes na maneira que querem ser. E quando são felizes é porque não são oprimidas por nada dentro do sistema”.