Why We Fund Where We Fund

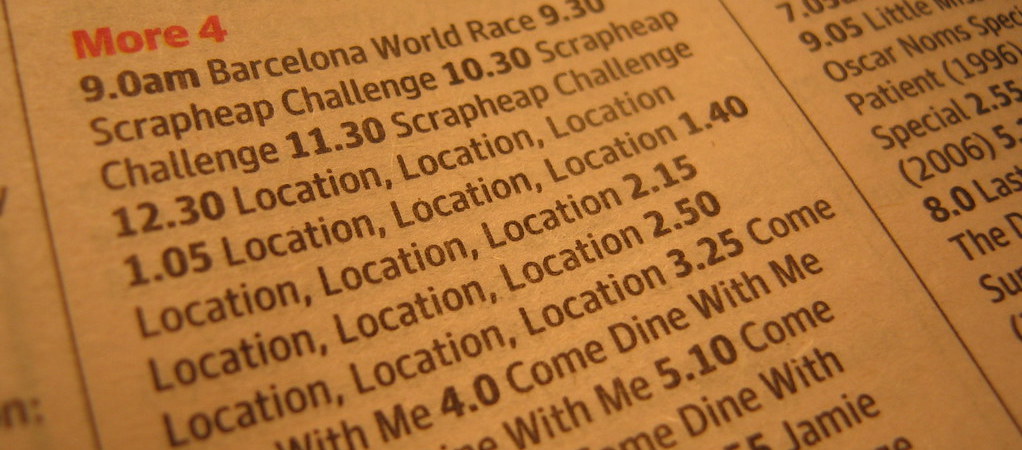

“Location, location, location”, goes the old real-estate mantra, and the importance of location should certainly not be undervalued when it comes to voluntary resource redistribution or philanthropy. When choosing which place(s) to pour monetary (and non-financial) resources into, some key considerations need to be made. For us at Guerrilla, the geographic questions we asked ourselves took us on an enlightening process of developing strategic rationale.

Neither Too Wide or Nor Too Narrow

When we kicked off the foundation, we knew we strategically wanted to focus on Europe, namely because all the team members were born and raised in different European countries and because we believed that there is enough cultural identity and similar sociopolitical pathologies on this continent to warrant a pan-European lens to our grassroots funding work.

One of our grant-making goals was and is to ‘fund the underfunded’. We find great value in going against the grain and employing an experimental approach to things, therefore funding neglected issue areas (e.g. community organising or care work), overlooked types of organisations (e.g. informal collectives) or underprivileged regions (Eastern & Southern Europe) has always been on top of our agenda. However, in the early days when we were just getting started, building credibility and know-how in the European activism ecosystem and funders scene, we started by funding where we were most familiar. We had more grantees in countries like the UK and Germany simply because we had already established trusting relationships with activists in these parts of Europe and a decent understanding of the political context.

Now, a few years into the game we have funded groups in 32 European countries and expanded our network of relationships. We respond with interest to requests from every corner of geographic Europe, however you need to be very bold or super relevant for the wider field of European systems change activism if you want to become a grant candidate from the UK or Germany nowadays. Greece, Italy and Poland were countries where, starting this year, we specifically reached out to local experts in order to get a better overview and recruit new applicants. Unlike in previous years, we now also aim for the top three countries we spent money in to be in CEE and south Europe.

The trick is to find that sweet spot between wider, regional, more diverse, cultural/political cross-pollination and narrower, more localised, rooted knowledge and networks of trust.

Countering Neocolonialist Giving

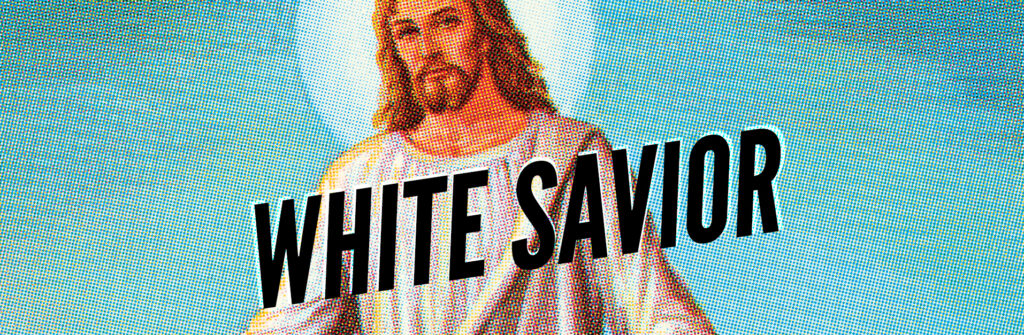

In the fictional universe of Star Trek, the Prime Directive is a guiding principle of Starfleet that prohibits its members from interfering with the natural development of alien civilisations. The Prime Directive protects unprepared civilisations from the dangerous tendency of well-intentioned starship crews to introduce advanced technology, knowledge, and values. Essentially, this means that, yes, you can be a meddling coloniser even if you have good intentions and, yes, you can sometimes unwittingly cause more harm than good.

This was the primary reason why we didn’t want to join the ranks of fossilised, messiah-complex foundations, which usually give off the taste of karma-cleansing of older, white, heirs or tycoons, who go out to ‘save’ the majority world. Accusations pointed at the Gates Foundation for promoting “corporate globalisation”, as well as appearing to be “a massive, vertically integrated multinational corporation, controlling every step in a supply chain that reaches from its Seattle-based boardroom … to millions of end-users in the villages of African and south Asia” are precisely the things we think is problematic about philanthropy. Teju Cole put it most aptly, “what innocent heroes don’t always understand is that they play a useful role for people who have much more cynical motives. The White Saviour Industrial Complex is a valve for releasing the unbearable pressures that build in a system built on pillage. We can participate in the economic destruction of Haiti over long years, but when the earthquake strikes it feels good to send $10 each to the rescue fund. I have no opposition, in principle, to such donations (I frequently make them myself), but we must do such things only with awareness of what else is involved. If we are going to interfere in the lives of others, a little due diligence is a minimum requirement.” So while we like to think we are taking steps to move away from the neocolonialist legacy of contemporary philanthropy, there is a constant need to check-in with oneself and local activists and philanthropic experts and to receive honest feedback from the communities one works with, to ascertain whether that continues to be true as time goes by.

Swimming Upstream

We consider European territories to be far from utopian, and they remain fertile ground for serious social justice reworking – especially since impact here, resonates far across the globalised chain. It is ludicrous to think “that for every $1 of aid that developing countries receive, they lose $24 in net outflows” and that “the flow of money from rich countries to poor countries pales in comparison to the flow that runs in the other direction”. Yet Jason Hickel’s research keeps hammering this point home, that overconsumption is killing the planet, and “instead of pushing poor countries to ‘catch up’ with rich ones, we should be getting rich countries to ‘catch down’”. Such research is exposing the deep hypocrisy at the heart of (primarily Western) philanthropic saviourism.

As explained in Dan Heath’s book, Upstream: The Quest to Solve Problems Before They Happen, we find guidance on how to find practical solutions for preventing problems rather than simply reacting to them. The challenge to treat symptoms quickly over a deeper, slower application of a cure, is not foreign to aid work and the funding of it. Do you provide Indonesian farmers with floating homes in the wake of climate-change-induced flooding, or do you target European and US corporations that are fuelling climate disasters through fossil fuel or coal extractivism, while decimating Indonesian forest for Western palm oil consumption demands? If most funders are funding symptoms, at least a handful need to be swimming Upstream and targeting the root causes of globalised pathologies.

It is a sobering realisation from the climate justice movement, that countries in the Global South, which have much smaller carbon footprints than their Occidental neighbours, are already reaping the dire consequences of climatic shifts. Europe is extremely far from having attained equitable prosperity and ecological balance since people far away are paying the price tag for this seemingly enviable continent to keep operating far beyond the planetary boundaries of consumption – the boundaries we should really be taking seriously.

Therefore, until our home region, Europe, doesn’t radically clean up its act regarding social and environmental injustices that keep originating here, and echoing disastrously across the globe, often with more harmful consequences much further afield, we will keep on funding grassroots activists building movements on European soil.

Geographic Equity & Inclusivity

Our geographic funding goals are to bring about more cross-border solidarity, cross-pollination of political vision, continuous exchange of campaigning skills, and to shift into post-competitive, participatory management of commonised resources. We also prioritise smaller towns over capitals and large cities, when it comes to our selection criteria, since big urban centers have much closer ties to philanthropic money, and so claim a disproportionate piece of the funding pie. Our mission is to keep finding ways of branching out, beyond existing resource oligopolies, and finding ways to be geographically inclusive while applying an equity-lens to our decision-making.

While the map is most definitely not the territory, we found that the best way to build useful localised and distributed knowledge is to listen, observe, travel (slowly, over land) and build a wildly diverse, trusted team of humans that will guide the resource distribution process in as fair and culturally-relevant a way as possible. The core message to other funders is to keep vetting their own answer to the question “why do you fund, where you fund?”