Lessons from New Orleans & a Commitment to Urban Social Movements

One sunny morning a couple of weeks ago in April, while attending the EDGE Funders Alliance‘s annual Conference in New Orleans, Louisiana, I woke up, grabbed a coffee and walked right into a dystopia together with about twenty other conference participants. Our walking tour was guided by two local activists: Imani from Blights Out and Shana from Displaced. These two amazing women not only blew our conferenced-out minds with a whirlwind of unsettling information, but also made sure that no one got killed in traffic, as they guided us through downtown New Orleans and the Tremé neighborhood. New Orleans’ short-circuited ten-second pedestrian lights really ensure that nobody considers walking a safe mode of transport!

The city of New Orleans has a painful history of exploitation, racism and displacement since its formation in the early 18th century and it is impossible to fully do it justice in one blog post. I felt compelled, however, to share a couple of especially striking points about New Orleans’ recent history as well as the creative forms of resistance that have emerged and can be related to city-based movements from around the world.

A hurricane that makes affordable housing & public services disappear

In August 2005, New Orleans was devastated by hurricane Katrina that flooded about 80% of the city and killed nearly 1,500 residents. The racism of the recovery process, however, seems to be the bigger, creeping disaster.

Where white neighborhoods were quickly rebuilt and even improved following Katrina, the mainly black neighborhoods all too often were not part of the often proclaimed ‘great comeback’ of the city. Largely intact social housing complexes were demolished during and after the clean-ups. Black homeowners received a fraction of their white counterparts in state recovery funds because their houses – located in mainly black neighborhoods – were appraised at a much lower value (for more details see e.g. here and here). The influx of well-educated white folks into the vibrant post-Katrina start-up scene coupled with mass tourism and the ‘Air BnB-ization‘ of entire neighborhoods is driving up rental prices, displacing and affecting mainly the Afro-American population in the face of persistent, massive income inequalities.

By 2015, rents and home values in the city had risen by over 50% as compared to pre-Katrina values. Eviction rates and segregation massively increased. Two statistics illustrate the current crisis the city is in:

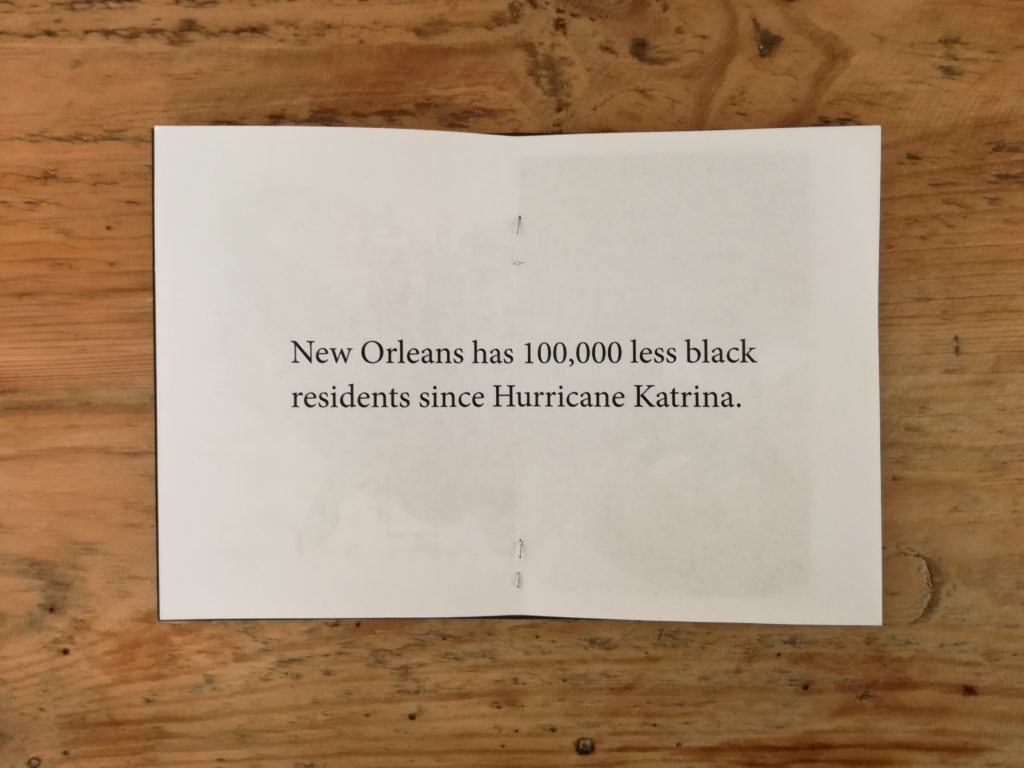

- New Orleans has 100,000 less black residents than before the hurricane.

- Air BnB and other so-called sharing economy short term rental sites list more properties than there are public housing units available.

What’s more, politicians also seem to have used the recovery years to completely privatise the provision of other essential services: The US’ oldest public hospital was replaced with a private one, the construction of which displaced many just-returned Katrina victims for a second time. Also, former public schools were reopened as so-called charter schools – privately run schools that are paid for by the state with tax money, ultimately benefiting the shareholders of their operators. According to Imani from Blights Out, today, New Orleans is the only state in the US that does not have a single public school left.

Blights Out’s name refers to blight as “A term originally used to describe diseased and browning plants appropriated by the State to describe dwellings occupied by poor, generally non-white, people.” The organisation estimates that between 20-50,000 properties in New Orleans are currently considered ‘blighted’ while about 33,000 affordable housing opportunities will be needed by 2025. Many of these properties are impossible to recover, not due to damage done by Katrina but due to the massive unforgivable debt they are burdened with. An individual house might have accumulated up to 100,000 $ in unpaid taxes, blight liens, clean up and demolition costs which makes it impossible to purchase, renovate and make it available on the housing market – except if you are an investor-backed developer. With creative campaigning, Blights Out criticises the city government for not making use of existing legislation that would have prevented this accumulation. They purchase billboard space to run their ‘Blights out for Mayor’ campaign or stage a ‘Theater of the Gentrified’ to draw attention to their call for housing justice. They also conduct ‘Design as protest’ workshops to bring together organisers, activists and creatives to re-imagine interventions in public space and organise housing-rights themed exhibitions.

Another shining example of resistance and creation of alternatives to the current extractive housing system is the Jane Place Neighborhood Initiative that we also briefly visited during our walking tour. They are a community land trust and housing rights organisation that models the provision of affordable, equitable housing to low income families while also fighting for justice and tenant rights more broadly, for example by publishing research and reports about the contribution of short term rentals to the rising housing prices.

Moreover, Jane Place is an amazing example for the creative energy, commitment and real community impact that can emerge from what in the beginning was a squatted warehouse that developed into a collective living, performance, art, and community space in 1999. A good lesson for the foundation participants of the tour to support such free spaces for community members to self-organise and develop a vision for their community.

‘Development Without Displacement’ & an Internationalist Municipal Movement

Two things gave me hope during this walking tour, despite the apparent doomsday scenario. First, the creative, unwavering resistance mounted by Blights Out, the Jane Place Neighborhood Initiative and many others.

Second, the fact that their core demand of ‘Development Without Displacement’ is echoed loud and clear by urban social movements around the world. Seemingly local struggles in places like New Orleans, Barcelona, Berlin or Cape Town increasingly grow together in their challenge to the structural inequalities and financialisation of the housing sector that are responsible for an increasingly unbearable situation for citizens in a variety of political and socio-economic contexts.

Today, housing-related struggles are one of the key spaces of social and political contestation in cities around the world. Like in Barcelona, they often are the seedbed for the emergence of municipal electoral platforms that challenge traditional politics and are strongly rooted in urban social movements. An internationalist municipal movement is arising and presents a model of political transformation that is based on emancipatory alternatives to neoliberal capitalism, right-wing populism and authoritarian rule.

The visit in New Orleans helped us at the Guerrilla Foundation to again realise the importance of contributing to the wave of housing-related struggles across Europe and the emerging network of municipal platforms, whether in government or not, that challenge the political and economic status quo.

I want to wrap up by referencing urban theorist Margit Mayer who dedicated her life’s work to urban social movements. In a recent podcast, she discusses the risk of appropriation of even radical social movements. As creators and inhabitants of cultural sites that also represent prime tourist destinations, urban social movements have in the past often been hijacked by the neoliberal city. Mayer argues that one of the successful strategies to prevent this from happening is to forge and maintain close alliances with traditionally marginalised groups like the homeless or evicted.

Besides being a note of caution for urban social movements, insights like this one inform our funding strategy. A case in point is our support for the European Action Coalition for the Right to Housing and the City, a network of grassroots urban struggles and one of our newest grantees: The City is for All who do a tremendous job at building alignment between (nearly) homeless people and middle class constituents in Budapest and beyond. The homeless and people threatened by eviction are the first and usually those most negatively affected by neoliberal city development. But in the end, this type of undemocratic, neoliberal version of ‘development’ harms us all.