The world of social change activism is full of heart, enthusiasm and good intentions, but it often unconsciously replicates the patterns and behaviours it seeks to eradicate. The desire to gain status, capital and power manifests under the guise of curated online personas which often lean on performative vulnerability and over-earnestness for coveted attention i.e. ‘buy my coaching services/course/book’, ‘here’s why what I have to offer is unique/better/best’ etc.

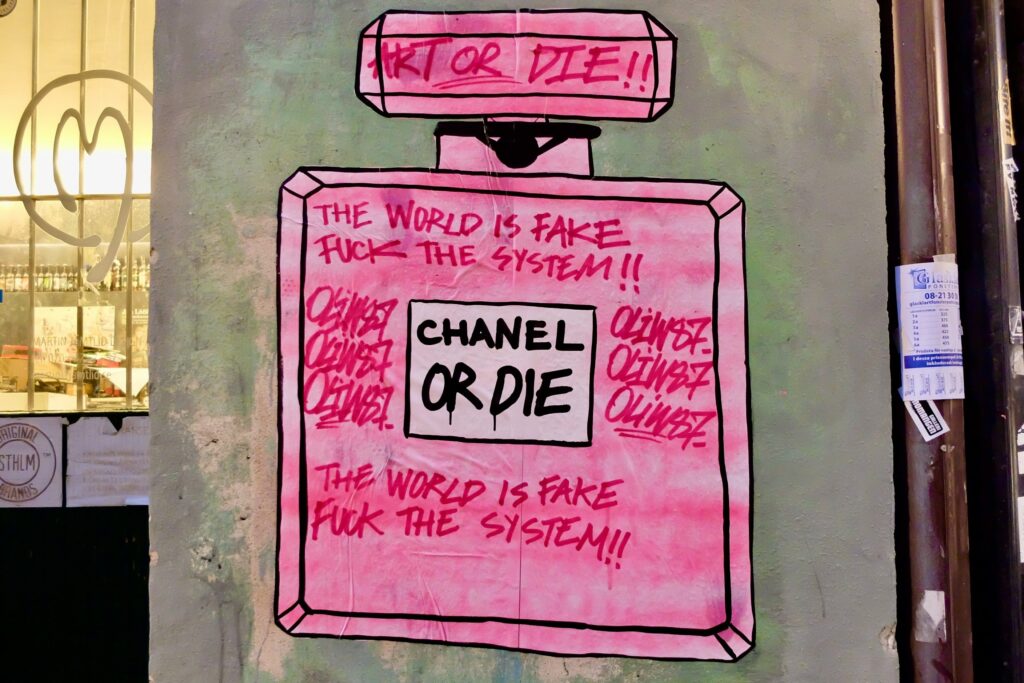

What is covert is harder to see and therefore harder to grapple with; it’s something we have to get honest about in the activist-sphere. The difficulty is, most of us have rent to pay and mouths to feed i.e. money to make, making it an unappealing conversation for those who rely on the commodification of their identity through ‘personal branding’. That’s not to say I believe people are manipulative or that sharing work isn’t a valid, honourable or necessary activity, just that we in the nonforprofit-verse need to better recognise our entanglement & culpability in this morass of contradiction. We are fuelled by the need to change systems collectively within an environment that acutely prohibits that change and instead quietly rewards and perpetuates individualism.

Despite increasing recognition that we must do this thing together, that is, unfuck the planet, our attention still turns towards the lone wolf, the ‘conscious celebrity’, the icon, the activist-come-messiah whose erudition and charisma enthral in a spectacle of infotainment and promises of a new world. Many nonprofits ache under the weight of ‘Founder’s syndrome’ in which the identity of the founder becomes the nexus of activity and public adoration. Gone is the seasoned expert, the experienced public intellectual, we’re now in the age of the ‘thought-leader’. The cult of personality prevails as activism becomes engulfed by celebrity, following the sombre footsteps of spirituality and all things ‘eco’ into the greenwashing machine. ‘Collaboration’ often supports the marketing power of individual personalities more than it supports communities. Unsurprisingly, most of these personalities are middle-aged, highly educated, highly privileged white men. There’s no beef here – I appreciate and respect the work of these men. The point I’m making is that there is a systemic pattern that over-privileges this particular type of human, and that is not only unfair, but also blindingly ignorant to other forms of equally valid, effective, and world-changing forms of knowledge fostered by not only women, but also other communities (human and beyond human).

Despite this, shifts are taking place. The collapse of institutions traditionally associated with knowledge ‘production’ is, on the one hand, a good thing. Corruption, dogma and exclusivity caused these environments to become misguided and blinkered towards other forms of knowing. On the other hand, this collapse has caused us to throw the expert baby out with the bathwater. What we’re left with is a lot of uncertainty about who said what, who gets to say what, where they get to say it, and what is being said in the first place. Sure, life is uncertain anyway, and our incessant impulse in the West towards perfect logical coherence is problematic in its own right, but we should not discard genuine, well-researched, heart-led expertise. This isn’t an anti-free speech sentiment or an expression of conservatism – it’s simply an acknowledgement that some ideas cause more harm than others when taken out of context.

The notion of the ‘thought-leader’, while perhaps more democratic in some ways (as in, anyone can gain a ‘following’ with the internet), somehow gives off eugenics vibes. Perhaps my subconscious is recalling the ‘thought police’ from Orwell’s 1984. We’ve known for years that we’re in a ‘crisis of sensemaking’, an ‘epistemological black hole’, and have since made effective strides towards recognising greater complexity in our efforts to unfuck the planet. Yet we are still defaulting to the few, the intellectual elite, which also happen to be proficient self-marketers, to tell us what to do next. It’s not that they don’t have useful things to share, nor that we, the ‘followers’, don’t ‘know’ – the issue in my view is that this relational dynamic pushes the capitalist and colonialist-inspired apotheosis of the individual, which disregards the power and agency of the collective, while turning human beings into ‘things’ for our consumption.

The consumer-capitalist paradigm teaches us that relationships are resources and that to have a valid life we must ‘complete ourselves’, often with a romantic partner who also doubles as our ‘saviour’, the redeemer of our incompleteness and hence flawedness. Christianity and Hollywood have sold us the story that we must be saved by this powerful and mystical ‘other’, someone who possesses something intangible, rare and valuable. This myth manifests in the deification of individuals who, granted, do have expertise (at least some do), but who also rely on selling their identity within the atmosphere of this ‘saviour’ complex. From having conversations with some of these people, I can report that it’s not fun for them, either. It’s exhausting and dehumanising as much as it feels good to be put on a pedestal.

Leadership is okay. Hierarchy, too, can also be okay. I want to make it clear that I’m not anti-expertise, power, or hierarchy. The natural world is full of these things – they are not inherently ‘bad’. The problem rears its head when we shift our focus from the content and context of what’s being said towards the identity of the individual saying it. Identity is important, especially now in light of intersectionality, but without this crucial socio-political-ethical context, identity becomes another product for our consumption. On the flip side (and there are many flip sides and contradictions here), inspiration is paramount in times like these. It is healthy to look towards those who have walked certain paths, had certain experiences and gained genuine know-how along the way. We are in dire need of elders in the West – but our grasping at this has become misguided. When healthy, inspiration can lead to action. When unhealthy, it can descend into this aforementioned hero-worship and subsequent apathy spurned by a false sense of safety stemming from the delusion that ‘this person will save us’. No one will save us. Perhaps, if we are lucky, the many will.

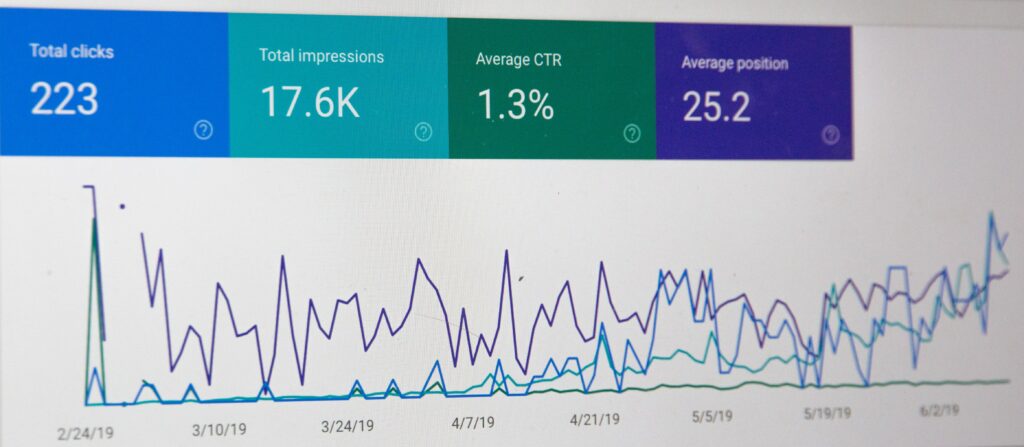

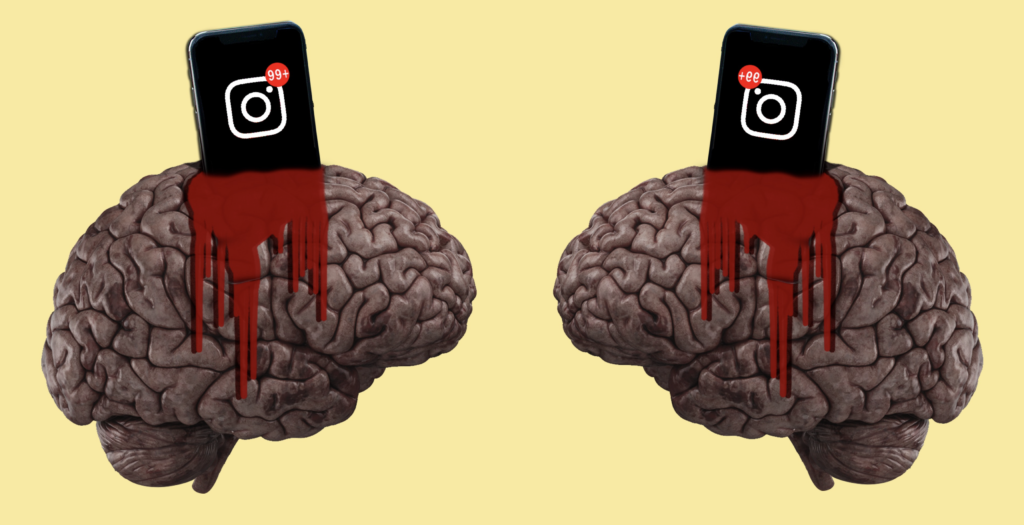

Equally, validation is not inherently ‘bad’. We want to be recognised for our efforts. We want feedback and affirmation. However, validation has, in many ways, become the ends as well as the means. The original ‘mission’ of many popular thinkers seems to have been buried as the intoxicating effects of public adoration take hold and the desire for more likes and clicks overwhelms. That said, the logic of increasing GDP (gross-domestic-personality), in part, makes sense.

1. Become a celebrity

2. Break into the mainstream

3. Inspire mass change.

The tools we have to do this, namely social media and platforms like YouTube, inevitably restrict the amount of ourselves we can put online, and social media culture actively discourages genuine vulnerability in favour of polished, performative vulnerability. It’s difficult for those trying to enact change not to fall into this trap. I’ve done it. Everything I say here is also a message to myself. We are mostly all just trying our best while at the same time attempting to keep our heads above water.

So how can we better navigate this spiky issue? Reorient people’s attention to the work itself. Steer away from a sole focus on personality. That’s not to say ignore personal context. This is crucial to include. Human problems (often) require human solutions, which require human emotions, which require human stories and so on. Question the intention behind sharing something and ask the question: is this adding value to other’s lives or am I just boosting my image and trying to sound clever? We are all, to some degree, traumatised beings who desire to come into contact with each other, to be seen, understood and cared for. This knowledge is important to hold whenever we enter the ‘public realm’ of appearances because it peels back the layers of our impulses, especially those which have become extractive and dependent on constant validation from others. Remember: our worth is not based on how many ‘paradigm-shifting’ offerings we can sell. Our intelligence cannot be measured in rhetoric. And, most importantly, our hearts and minds are not products.

Hannah Close is a curator, writer and photographer. She designs courses for the transformative education platform advaya, and recently collaborated with the marine biologist and philosopher Dr Andreas Weber on the ‘Ecology of Love’. She is currently making a documentary called ‘Islandness in the Anthropocene’.