paradoxical psychology of political action

The biggest challenge in trying to change the world is the main material: people. We’re beautifully fucked up, weird and unreliable. Even the best among us are ruled by profound and, frankly, bonkers passions, delusions, and fears. And thankfully so: that’s what makes life beautiful. But when it comes to working together in social movements things can easily get out of hand.

We (two friends, scholars and organizers) started Sense & Solidarity to offer a platform for movements to learn about what actually works to change hearts and minds in the struggle for collective liberation, and to offer workshops, classes and a podcast that explore the gnarly, wacko and heartbreakingly human side of what makes the struggle for a radically different world succeed (and, more often, fail).

Max is long-time movement organizer, a writer and educator who specializes in the politics of the imagination, including the radical imagination that makes it possible for people to fight for different futures. Sarah is a public intellectual whose writing and broadcasting focus on what the latest research in cognitive sciences can teach the left about politics.

In this post, we’ll tell you a little bit about some of the core themes we cover in our courses, workshops and podcast, and also how we think about Sense & Solidarity as an initiative that provides and fosters “infrastructure” for movements for collective liberation.

The Radical Imagination

The radical imagination is the force that enables us to imagine the world could and should be different, and that animates solidarity and struggle against dominant power relations.

But often the term is surrounded by a haze of good feelings which can be profoundly misleading. Most organizers are faced with the challenges of apathy, resignation, hopelessness and depression when they try to win people over to their cause. It’s tempting to think that “if only” the radical imagination were in greater abundance, things would be easier, people would be inspired, take action, join the movement.

It’s easy to make the idea of the radical imagination into an example of what French psychoanalytic thinker Jacques Lacan, writing about individual psychology, called objet petit a: the thing we convince ourselves we lack in order to make sense of ourselves. If only I had the job, the relationship, the family I wanted, then I wouldn’t be such a fuck-up… If only there was more imagination at work in our movements, surely we’d have a revolution by now… but it is precisely this longing for an impossible thing outside of ourselves that keeps us in a stagnant, unchanging state, a state in which we might be miserable, but comfortably so. After all, it’s easier to be predictably unhappy than to take that risk of changing, especially when that risk means putting our sense of self, our sense of agency, our sense of safety on the line.

In this case, we keep wishing for the radical imagination to appear and change things, precisely so we don’t have to question some of the comfortable patterns that keep our movements stagnant.

One of these patterns is that many activists are convinced that people can grow their radical imagination by being exposed to the right books, hearing the right speeches, or learning real history. All that’s important, but in fact the imagination transforms when people act, and act together. The radical imagination, as Max argued in his book on the subject (co-authored with Alex Khasnabish), is not something individuals have, like a private walled garden in their minds. Rather, the radical imagination is something that people do, and do together. We “do” the radical imagination when we struggle collectively – it “sparks” in the moment when people say “no” together to the reigning state of affairs.

It’s tempting for us to imagine that, in order to inspire the radical imagination, we need bold, utopian or at least hopeful visions of a better society, or of concrete “wins” that common people can envision that will make the sacrifices of activism and organizing worth it. As important as these are, the spirit and collective act of refusal is even more useful: when people say “no” together they are creating a different world, a world where our dignity and our right to create a different future are not violated, a world of possibility. Refusal is not, in and of itself, enough, but it is essential as a catalyst because it triggers actions in common, and in those actions we prove to ourselves we are capable of creating something else.

Meanwhile, if we want to be able to cultivate a more substantial vision of a better future, it will only emerge from the actions we take in the here and now. The human imagination is among the most powerful and beautiful gifts we possess, but its range is limited to small leaps from what we already know and experience. This is why, for example, many revolutions have begun with what appear to be demands for small reforms that fit within the scope and idiom of the reigning order (“remove the King’s evil advisors,” “restore the fuel subsidies,” “tax the rich”). But when people gather and experience what it means to cooperate, collaborate and world-make together, when we come to recognize our latent powers to imagine and to make our imaginations manifest, the radical imagination can (but does not always) accelerate in a positive feedback loop with the mobilization.

In our workshops, we focus on the lessons of history and the present to help us develop theories and tools for cultivating the radical imagination.

Cognitive Dissonance

A lot of what we do at Sense & Solidarity is explore theories and methods for changing people’s minds. No matter what strategy we might take to try and change the world, it’s going to involve convincing people to see the world our way and to do something about it. But this is easier said than done, and one of the lessons that recent cognitive sciences teach (and that is the focus of Sarah’s book, coming out in 2025) is that just talking at people and providing good, rational arguments and counterarguments rarely actually works, or at least not the way they tend to imagine.

Sarah’s research focuses on the many reasons why “debate” doesn’t often work. This includes the way that a theory of cognitive dissonance can help explain why so many people are deeply invested in ideological ideas that, in fact, justify and reproduce their own oppression. For example: those who are oppressed in capitalist systems might still advocate for such a system or even feel excited by the idea of being an “entrepreneur” in the gig economy.

Cognitive dissonance describes the discomfort Western subjects in particular experience when faced with a contradiction between their beliefs and their actions. All of us experience this discomfort regularly. We might, for example, know that flying on planes harms the environment but we do it anyway, and then come up with justifications afterwards (Max and Sarah are both guilty as charged!).

It’s important for movement organizers to understand how this works, because it’s all around us, all the time, especially when people’s actions (or inactions) contribute to systems of oppression and domination. Most of the time, the dissonance is invisible, but when it is revealed (for example, by activists blocking an airport runway) it can lead to profound discomfort. When people experience this discomfort, they often respond either with a rationalization or by engaging in a form of confirmation bias.

Rationalization is when we use reasons (often quite intelligent or convincing ones) to justify maintaining our current beliefs or behavior, even if these are not appropriate. We might say “smoking is actually good for me because it helps me lose weight.” Or we might reason that “this plane is going to take off with or without me, so what I’m doing doesn’t really matter.”

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms or supports one’s prior beliefs or values. We might say “I heard that the latest science says drinking alcohol is bad for me, but these other studies say it’s actually healthy…” or “I’ve read dozens of books on why communism is destined to fail, so don’t even bother talking to me about it.”

Dissonance theory generally suggests that, when faced with a conflict between our beliefs and our actions, we’ll usually (fairly unconsciously) shift our beliefs to match our actions. This is so even (perhaps especially) for people who believe themselves to be very principled and who would claim that their actions always follow their beliefs. After all, changing our actions is harder, especially because we can’t retrospectively change actions we’ve already been engaged in. Most of us, by necessity, engage in actions that are part of harmful systems: we live in a society where there are few alternatives to planes for long-distance travel, where many of us are compelled to work for organizations that do harmful things, and where avoiding driving a car, eating commercially farmed food, or buying a phone or clothing manufactured under wretched conditions is extremely difficult or costly.

Living in a world where our compulsory actions contradict our values is profoundly uncomfortable. And so many of us adjust our views to reduce the discomfort by rationalising that these systems are necessary or unavoidable, if not actually good. In fact, the psychologist John T. Jost has offered System Justification Theory as a way to explain why those who are most oppressed by a system are often the most likely to say that the system is unavoidable or just: believing the world has to be this way. Those who are better off in a system may face less of a contradiction and feel less need to rationalise the unjust-ness of the system.

What does this mean for activists and organizers?

Arguing with people in order to change their views is rarely effective. But enlisting possible supporters to join a movement in small ways could lead to a relatively large shift in their views and commitment to a cause. Remember: people’s beliefs tend to follow their actions. If we can get people involved in a small way (“hey, you don’t have to stand on the front lines or speak at the press conference, but can you help me prepare and serve the lunch?”), they will tend to justify it to themselves and a virtuous circle can emerge.

Another implication is that showing people there are other possible ways of living can be very important. It is unlikely that people will shift their views unless they see a set of possibilities for action that can align with a new set of beliefs. This is why systems of mutual aid can often be a starting point for people to believe in collaborative economic systems rather than systems motivated only by competition and self-interest.

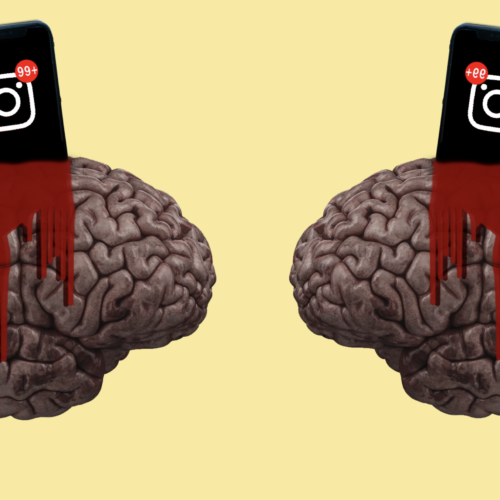

Taking cognitive dissonance theory, and the broader cognitive sciences, seriously is important for the left. This is true even though many of us rightly tend to be uncomfortable with allegedly scientific ideas of “human nature” that usually seem to reinforce the competitive capitalist status quo, or that seem to take Western norms for universal truths. But there is a wealth of ideas out there that can help us in our struggles. And we also need to be aware that the right, as well as many corporations, are eagerly using these approaches to manipulate people towards their ends.

At Sense & Solidarity we want to engage this kind of thinking critically, but with an eye to using it to change the world.

Building Infrastructure for Movements

Sense & Solidarity is one of a growing number of efforts around the world to build alternative infrastructures to encourage critical thinking, radical ideas and transformative research in solidarity with movements for collective liberation.

Our specialization is what we might call the “psychology” of movements and politics, although by that we mean something much broader: the way our social body-minds work, the way our imaginations function, the way our all-too-humanness enables and gets in the way of working together and changing the world.

To do that, we offer online and in-person workshops, ranging in duration from one evening to a full week. In 2024 we ran a 4-day school in Berlin in May and will run a 3.5-day school in London in November, with plans afoot for similar events in the US in early 2025. We try and keep costs as low as possible, and offer subsidies.

We’re also producing What Do We Want? A research-driven but also chatty podcast (due out in October 2024) about the weird, wild and wonderful things that bring movements together… and drive them apart, including lessons about the radical imagination and cognitive sciences such as above.

Additionally, we host retreats and skill-shares for writers in the hopes of fostering a new generation of public intellectuals who know how to make radical ideas irresistible using all the technology and techniques at our disposal.

We do all this in part because we have very little optimism that the university will be a haven for radical thought for much longer (if it ever was). Neoliberal cutbacks and neoreactionary attacks have shredded the university’s capacity to foster knowledge and people that are useful for real struggles for collective liberation. It’s hard to see how this trend will be reversed. It’s more important than ever that intellectuals and movement organizers collaborate on creating, sustaining and cultivating spaces and times for learning, reflection, theorizing and strategizing.